How the ear works

How does the human ear work? These clear diagrams, information and subtitled videos explain all about the ear.

How does the human ear work? These clear diagrams, information and subtitled videos explain all about the ear.

The anatomy of our hearing system is complex. It can be broadly divided into two parts – the peripheral hearing system and central hearing system.

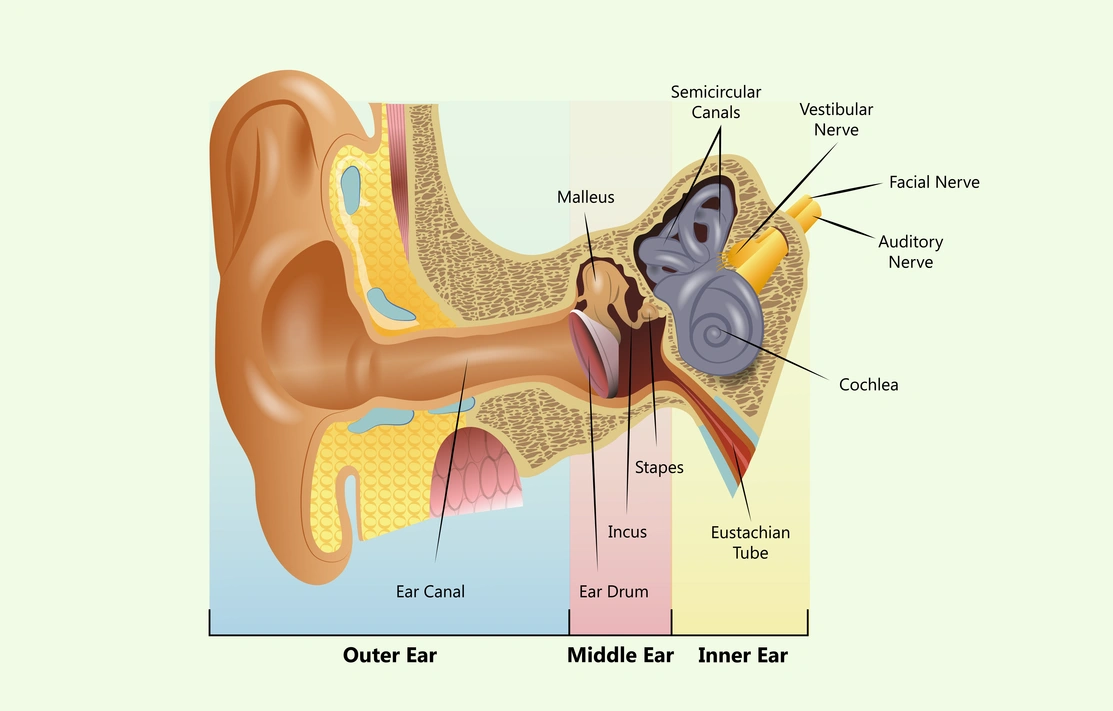

The peripheral hearing system consists of three parts – the outer ear, middle ear and inner ear.

The outer ear consists of the pinna (also called the auricle), ear canal and eardrum. The middle ear is a small, air-filled space containing three tiny bones called the malleus, incus and stapes. Collectively they are known as the ossicles. The malleus connects to the eardrum, linking it to the outer ear. The stapes (smallest bone in the body) connects to the inner ear.

The inner ear has two main sections - the cochlea for hearing and the vestibular system for balance.

The hearing part of the inner ear is called the cochlea. This comes from the Greek word for ‘snail’ because of its distinctive coiled shape. The cochlea contains many thousands of sensory cells called hair cells and is connected to the central hearing system by the hearing or auditory nerve. The cochlea is filled with special fluids which are important to the process of how the ear works.

The central hearing system is responsible for interpreting the auditory information such as frequency, volume and location. It consists of the auditory nerve and a complex pathway through the brainstem and onward to the auditory cortex of the brain.

The physiology of how our ear works is also complex. It is best understood by looking at the role played by each part of our hearing system.

Soundwaves are vibrations in the air all around us. These are collected by the pinna (located in the outer ear) on each side of our head.

From here, the soundwaves are funnelled into the ear canal and make the eardrum vibrate. The eardrum is extremely sensitive and can detect even the faintest of sounds.

The eardrum vibrations, caused by soundwaves, move the ossicles (the chain of tiny bones in the middle ear called the malleus, incus and stapes).

The stapes, the last of these three bones, sits in a membrane-covered window in the bony wall. This area separates the middle ear from the cochlea in the inner ear. As the stapes vibrates, it makes the fluid in the cochlea move in a wave-like manner, stimulating the hair cells.

Remarkably, the hair cells in the cochlea are tuned to respond to different sounds based on their pitch or frequency. High-pitched sounds stimulate hair cells in the lower part of the cochlea. Low-pitched sounds stimulate hair cells in the upper part of the cochlea.

Each hair cell detects the pitch or frequency of sound to which it’s tuned to respond and generates nerve impulses. These travel instantaneously along the auditory nerve.

These nerve impulses follow a complicated pathway in the brainstem before arriving at the hearing centres of the brain, the auditory cortex. This is where the streams of nerve impulses are converted into meaningful sound.

All of this happens within a tiny fraction of a second, almost instantaneously after sound waves first enter our ear canals. It is very true to say that, ultimately, we hear with our brain.

Courtesy of MED-EL

This video requires marketing cookies to be viewed. Please accept cookies to view this video content.

Hearing well depends on all parts of our auditory system working normally. This is so that sound can pass through the different parts of the ear to the brain to be processed without any distortion.

The type of hearing problem you have depends on which part of your auditory system is not responding well.

Registered charity in England and Wales no. 293358 and in Scotland no. SC040486. Royal Patron HRH The Princess Royal.